It is just shy of £200 million. To be precise, it is £199.6 million. “It” is the difference in turnover between Manchester United and any other club who were not in last season’s Champions League. Tottenham came closest. Their revenue was less than half of United’s £395.2 million.

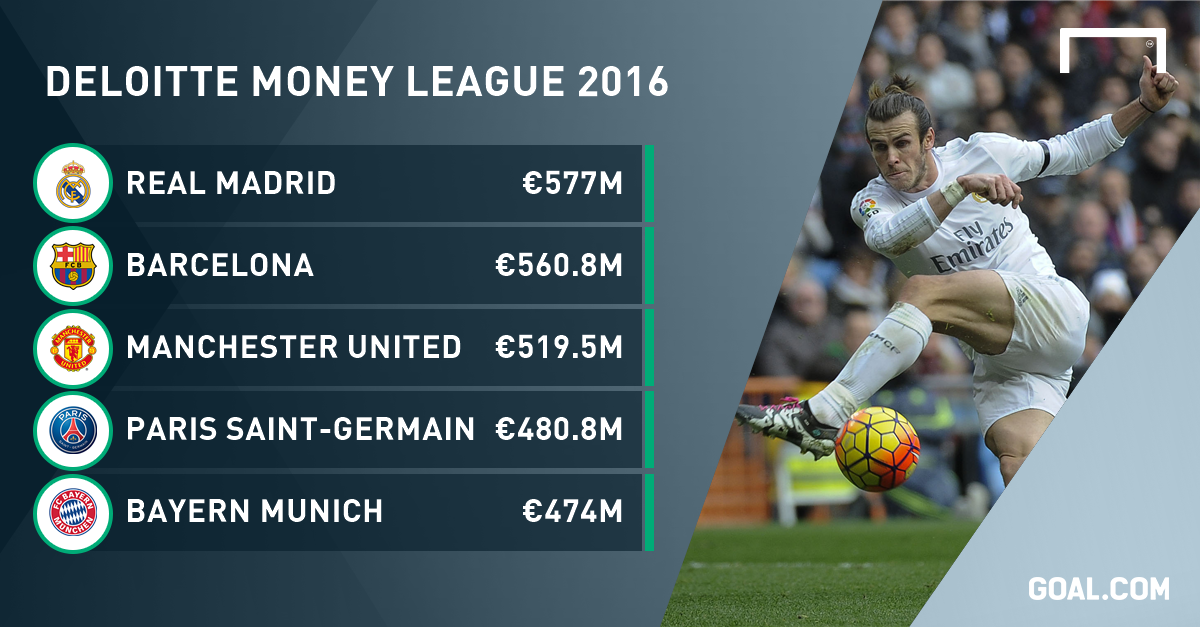

Because the stand-out feature of the Deloitte Football Money League is not that Real Madrid are top, for an 11th successive year, or even that Barcelona overhauled United to claim second place. They did, after all, do a Treble. No, it is the fact that United, deprived of a money-spinning invitation to the Champions League, still had the third biggest income in world football. They did so despite not participating in the Europa League either, or without playing a home game in the Capital One Cup.

This was the aberration, the one-off, the year United’s revenue dipped by almost £40 million. It was still £35 million bigger than Bayern Munich’s, £75 million larger than Chelsea’s, about the same as Juventus and Roma’s put together. It was some £120 million more than AC Milan’s and Inter’s combined.

It showed that United are the global game’s true financial superpower. Their turnover is set to crash through the £500 million mark this year, aided by their record 10-year £750 million kit deal with Adidas. When the Premier League’s most lucrative broadcast rights deal kicks in the following season, it may approach the £600 million mark. Assuming, that is, that United even qualify for the Champions League.

Because the commercial team are outperforming the football team right now. They have done throughout Louis van Gaal’s reign and David Moyes’ tenure. Ed Woodward’s record in the transfer market has brought criticism but he is the Lionel Messi of the sponsorship and partnership world.

The executive vice-chairman could sell Manchester United-branded snow to the Inuit, but with the proviso that he had concluded separate deals for the Canadian, Alaskan and Greenlandic markets, thus increasing his profits. They are huge even without the kind of flagship signing who would make United still more attractive to sponsors. Deloitte’s report cites the “underlying strength of the business model, in particular its commercial operations.” The language is restrained but the sentiments are serious. Manchester is becoming football’s money capital.

But it does bring the question of when United will punch their financial weight on the pitch. Van Gaal has been able to invest £285 million on new recruits. Summer transfer budgets of around £150 million seem here to stay. The Dutchman’s team still languish in fifth place after playing plodding football. United still have not mounted a title challenge or secured any silverware, the Community Shield and pre-season tournaments apart, since Sir Alex Ferguson retired.

It is underachievement on a colossal scale. The worrying aspect for United’s rivals is that, logically, it cannot continue. Sooner or later, pounds will be translated into points. At some stage, there must come a time when budgets alone will dictate that a Champions League elimination at the hands of Wolfsburg and PSV Eindhoven becomes impossible, rather than merely ignominious. In the meantime, if Van Gaal is in any doubt about what an undistinguished job he is doing, he only needs to look at the figures.

BIG SPENDERS | Manchester United have splashed out £285 million on new players under LVG

And if those on mainland Europe are feeling pessimistic, this table should depress them further. It is not merely the sight of five English clubs in the top nine, or nine in the top 20. The Premier League’s increasing financial supremacy is reflected in the small print. The clubs with the 22nd-29th biggest turnovers represent a clean sweep: Southampton, Aston Villa, Leicester, Sunderland, Swansea, Stoke, Crystal Palace and West Bromwich Albion.

In other words, everyone who stayed up in England had a greater revenue than supposedly bigger clubs, including some of Europe’s traditional giants like Fiorentina, Lazio, Napoli, Valencia, Marseille, Lyon, Porto, Benfica, Hamburg and Ajax.

Under such circumstances, it becomes more understandable that Marseille’s two best players, Dimitri Payet and Andre Ayew, now ply their trade for West Ham and Swansea respectively. In the modern economy, they are wealthier clubs than the 10-time champions of France and 1993 European Cup winners.

No matter that capacity crowds at Upton Park and the Liberty Stadium could fit comfortably into the cavernous Stade Velodrome or that Marseille is France’s third-biggest city. But matchday revenue is far less significant than broadcast and commercial income now. The season-ticket holder is an ever decreasing factor. The Premier League is reshaping football’s finances, tilting the balance from historic forces to mid-table sides on a comparatively small island.

United are their role models. Not in the style of play or the results on the pitch, but on the balance sheet. Yet if they elbow Real and Barcelona aside to top this particular table next year without actually improving on the pitch, it will merely prompt more questions. Such as: shouldn’t the team actually be a bit better?

No comments:

Post a Comment